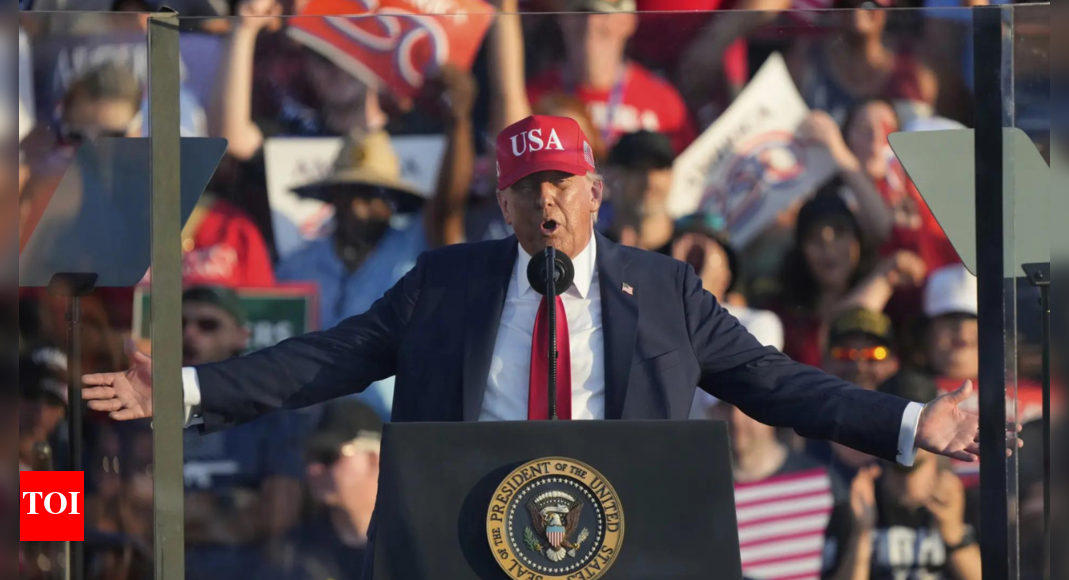

President Donald Trump speaks at the Saudi-U.S. Investment Forum at the King Abdulaziz International Conference Center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Photo: AP)

Washington: Saudi royalty and American billionaires were in the front row for a speech in Riyadh where President Donald Trump condemned what he called past U.S. interference in the wealthy Gulf states.

Gone were the days when American officials would fly to the Middle East to give "you lectures on how to live, and how to govern your own affairs," Trump said at a Saudi investment forum this week. No one in the audience sat closer, or listened more intently, than Saudi Arabia's crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman. Ordinary Arabs listened, too, including Saudi journalists, rights advocates, businesspeople, writers and others who had fled the kingdom.

Their fear: Trump's words underlined a message that the United States was pulling back from its longtime role as an imperfect, sporadic but powerful advocate for human rights around the world. "It was painful to see," said Abdullah Alaoudh, whose 68-year-old father, a Saudi cleric with a wide following, was among hundreds of royals, civil society figures, rights advocates and others jailed by Prince Mohammed in the first years of his rise to de facto ruler.

Saudi Arabia has since freed many of those people in what groups say is the crown prince's improved human rights record following past international criticism and isolation. But Abdullah's father, Salman Alaoudh, is among the many still behind bars. Trump was speaking directly to the prince - "the person who tortured my father, who has banned my family" from leaving the kingdom, said Abdullah, who advocates for detained and imprisoned people in Saudi Arabia from the United States. The Saudi embassy did not immediately respond to messages seeking comment. A White House spokeswoman, Anna Kelly, said Trump's speech "celebrated the ever-growing partnership between the United States and Saudi Arabia" and a Middle East working toward peace. Kelly did not respond to a question about whether the president had raised human rights issues with Gulf leaders. A State Department spokesman, Tommy Pigott, called Trump's discussions with Gulf leaders private. Less attention than usual on human rights Trump's first major trip of his second term - also including Qatar and the United Arab Emirates - drew far less attention to human rights than is typical for U.S. visits to autocratic countries with spotty records on free speech, fair trials and other rights. Human rights groups posted concerns about the Gulf countries, but some refrained from more vocal objections. Saudi exiles in the U.S.

also skipped the usual pointed comments on social media. And the administration faced few of the typical questions on whether a visiting president had used the trip to press for the release of detained Americans or imprisoned activists. That's partly due to human rights improvements in Saudi Arabia, groups say. But the silence also reflects what some organizations call a worsening human rights picture in the United States. Ibrahim Almadi, a Florida man seeking U.S. help getting his father home from Saudi Arabia, said he tried in vain to score a commitment from a Republican lawmaker or other official to urge Trump to raise his father's cause. His now 75-year-old Saudi American father, Saad Almadi, had been jailed over critical tweets about the Saudi government and now is under an exit ban from the country. "It is a love relationship between Trump and MBS," the son said.

One mention of the case to Trump, then one comment by Trump to the Saudi crown prince, and "I will have my father back." Some voices have gone silent Some Saudis who fled to the U.S. say they are pulling back from social media and any public criticism of Saudi officials, fearing the same detentions and deportations faced by some immigrants and pro-Palestinian protesters under the Trump administration. Democracy in the Arab World Now - the nonprofit founded by Jamal Khashoggi, the U.S.-based journalist killed at the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul - is advising Arabs with unsettled immigration status in the U.S. to "be cautious when they travel, to be thoughtful about what they say," executive director Sarah Leah Whitson said. The U.S. intelligence community said the crown prince oversaw the 2018 plot, while he has denied any involvement. The killing of Khashoggi, who used his Washington Post column to urge Prince Mohammed to institute reforms, led then-President Joe Biden to pledge to make Saudi royals into pariahs. But soaring U.S. gasoline prices in 2022 spurred Biden to visit the oil-exporting giant, where he had an awkward fist bump with the prince. In his second term, Trump has tightened his embrace of Prince Mohammed and other wealthy Gulf leaders, seeking big investments in the U.S., while Trump's elder sons are developing major real estate projects in the region. The human rights record in Saudi Arabia Burned by the condemnation and initial isolation over Khashoggi, Prince Mohammed has quietly released some of those imprisoned for seeking women's right to drive, for critical tweets, for publicly proposing Saudi policy changes and more.

The prince also has liberalized legal and social conditions for women, part of a campaign to attract business and diversify Saudi Arabia's economy. But many others remain in prison. Thousands, including Almadi, face exit bans, rights groups say. Those organizations cite another reason that activists are staying quieter than usual during the trip: the United States' own human rights reputation. Besides deportations, Whitson pointed to U.S.

military support to Israel during its 19-month offensive against Hamas in Gaza, which has killed thousands of civilians. The Trump administration says it's trying to secure a ceasefire. Americans faulting another country's abuses now "just doesn't pass the laugh test," Whitson said. "The United States does not have the moral standing, the legal standing, the credibility to be chastising another country at this moment in time." (AP) AS

1 month ago

71

1 month ago

71

English (US)

English (US)