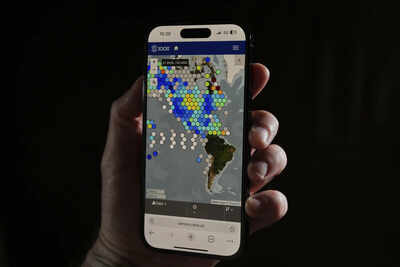

Capt. Ed Enos makes his living as a harbor pilot in Hawaii, clambering aboard arriving ships in the predawn hours and guiding them into port. His world revolves around wind speeds, current strength and wave swells. When Enos is bobbing in dangerous waters in the dark, his cellphone is his lifeline: with a few taps he can access the Integrated Ocean Observing System and pull up the data needed to guide what are essentially floating warehouses safely to the dock. But maybe not for much longer. President Donald Trump wants to eliminate all federal funding for the observing system's regional operations. Scientists say the cuts could mean the end of efforts to gather real-time data crucial to navigating treacherous harbors, plotting tsunami escape routes and predicting hurricane intensity. "It's the last thing you should be shutting down," Enos said. "There's no money wasted.

Right at a time when we should be getting more money to do more work to benefit the public, they want to turn things off. That's the wrong strategy at the wrong time for the wrong reasons." Monitoring system tracks all things ocean The IOOS system launched about 20 years ago. It's made up of 11 regional associations in multiple states and territories, including the Virgin Islands, Alaska, Hawaii, Washington state, Michigan, South Carolina and Southern California.

The regional groups are networks of university researchers, conservation groups, businesses and anyone else gathering or using maritime data. The associations are the Swiss army knife of oceanography, using buoys, submersible drones and radar installations to track water temperature, wind speed, atmospheric pressure, wave speeds, swell heights and current strength. The networks monitor the Great Lakes, U.S.

coastlines, the Gulf of Mexico, which Trump renamed the Gulf of America, the Gulf of Alaska, the Caribbean and the South Pacific and upload member data to public websites in real time. Maritime community and military rely on system data Cruise ship, freighter and tanker pilots like Enos, as well as the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard, use the information directly to navigate harbors safely, plot courses around storms and conduct search-and-rescue operations. The associations' observations feed into National Weather Service forecasts. The Pacific Northwest association uses tsunami data to post real-time coastal escape routes on a public-facing app. And the Hawaii association not only posts data that is helpful to harbor pilots but tracks hurricane intensity and tiger sharks that have been tagged for research. The associations also track toxic algal blooms, which can force beach closures and kill fish.

The maps help commercial anglers avoid those empty regions. Water temperature data can help identify heat layers within the ocean and, because it's harder for fish to survive in those layers, knowing hot zones helps anglers target better fishing grounds. The regional networks are not formal federal agencies but are almost entirely funded through federal grants through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The current federal budget allocates $43.5 million for the networks. A Republican bill in the House natural resources committee would actually send them more money, $56 million annually, from 2026 through 2030. Cuts catch network administrators by surprise A Trump administration memo leaked in April proposes a $2.5 billion cut to the Department of Commerce, which oversees NOAA, in the 2026 federal budget. Part of the proposal calls for eliminating federal funding for the regional monitoring networks, even though the memo says one of the activities the administration wants the commerce department to focus on is collecting ocean and weather data. The memo offered no other justifications for the cuts. The proposal stunned network users. "We've worked so hard to build an incredible system and it's running smoothly, providing data that's important to the economy. Why would you break it?" said Jack Barth, an Oregon State oceanographer who shares data with the Pacific Northwest association. "What we're providing is a window into the ocean and without those measures we frankly won't know what's coming at us.

It's like turning off the headlights," Barth said. NOAA officials declined to comment on the cuts and potential impacts, saying in an email to The Associated Press that they do not do "speculative interviews." Network's future remains unclear Nothing is certain. The 2026 federal fiscal year starts Oct. 1. The budget must pass the House, the Senate and get the president's signature before it can take effect. Lawmakers could decide to fund the regional networks after all. Network directors are trying not to panic. If the cuts go through, some associations might survive by selling their data or soliciting grants from sources outside the federal government. But the funding hole would be so significant that just keeping the lights on would be an uphill battle, they said. If the associations fold, other entities might be able to continue gathering data, but there will be gaps. Partnerships developed over years would evaporate and data won't be available in a single place like now, they said. "People have come to us because we've been steady," Hawaii regional network director Melissa Iwamoto said. "We're a known entity, a trusted entity. No one saw this coming, the potential for us not to be here."

1 month ago

76

1 month ago

76

English (US)

English (US)